Christian Dior’s New Look (Image Credit: Vogue.com) and “Tradwife” aesthetic (Image Credit: People.com)

Paris in the late 1940s saw immense changes to its city, both socially and visually. Women traded in their work boots for heels, once again hearing the clack of each step against the cobblestone streets. During World War II, luxuries were not afforded under the restrictions of wartime rations.

1943 Bergdorf Goodman Sketch (Image Credit: The Met Digital Collections at metmuseum.org)

As women entered the workforce during the war, slim shapes and sharp lines characterized global feminine styles for fear of excess waste in garment production. Assuming occupations of those called to war, women also visually emulated the (then) masculine nature of labor by donning utility suits and trousers.

But after the war’s end, the desire to grasp some semblance of normality plagued the world, as men returned to work. In post-war France, fashion houses scrambled to produce visions of extravagance and uniqueness: a new look that would define a generation and social period—one of recovery, celebration, and restoration.

Christian Dior’s New Look (Image Credit: Vogue.com)

In 1947, French designer Christian Dior debuted a characteristic look, an exaggerated revival of pre-war silhouettes. Coined the “New Look” by fashion writers, the design’s slim waist accentuated the extravagant billowing pleats of its skirt. The rigid shoulders of wartime suits were softened into curving lines, while sharpness instead shaped the waist into petite restriction. The style thus became a physical embodiment of the burgeoning post-war fashion markets and global economies. In its curvaceous allure, the “New Look” not only cemented Paris as an unwavering influence on global fashion but also represented a revival of the couture industry as a whole.

A pattern for a 1950s house dress (Image Credit: Pinterest.com)

However, a style of dress that was made to exemplify a period of independence, was soon mobilized into a symbol of social confinement.

As the American ready-to-wear industry continued to develop in the 1950s, Dior’s “New Look” became synonymous with the vision of suburban motherhood and wifehood. The “house dress,” a shirtwaist dress often cinched at the waist and full in the skirt, was seen as suitable for all duties of the suburban household: cooking, cleaning, and silence.

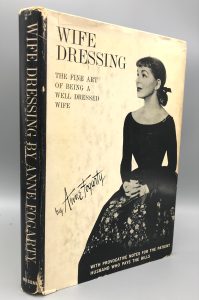

Anne Fogarty’s book, Wife Dressing: The Fine Art of a Well-Dressed Wife (Image Credit: Panoplybooks.com)

In her 1959 book, Wife Dressing: The Fine Art of Being a Well-Dressed Wife, fashion designer Anne Fogarty described the simple austerity of the shirtwaist dress as ideal for one’s role in the home.

In this light, the “New Look” is a balance of constraint and freedom, as the waist cinches the liberating movement of its twirling pleats. With every flounce of its skirt, the garment models the cultural ideals of femininity as a normalcy in Western society. For the housewife, it accentuates the curves of her form into almost cartoonish shapes. The “New Look” isn’t a dress. It’s a body in motion, constructed by a male designer, and dictated into idealized, silhouetted perfection.

The “New Look” is undeniably beautiful; it revolutionized and revived the economy of global haute couture. Two things can be true at once. This hyper-feminine style overshadowed the freedoms granted to women during World War II. Used against the image of equality and progression in the 1950s, the “New Look”—while chic—was detrimental to the garmenting of women in post-war societies, confining them to visions of purity and softness.

Influencers who have embodied the “tradwife” aesthetic (Image Credit: People.com)

It’s hard to ignore how this exaggerated silhouette has been weaponized throughout history. In recent years, the style has seen a rise in popularity with fluctuating trends, often in tandem with the rise in political conservatism in the United States. The “tradwife” aesthetic—one that preaches modest dress, hours working in the kitchen on homemade meals, and images of rural sanctuary in a child-filled home—riddled the internet in the months leading up to the 2024 presidential election. Characteristic of the popularized style, the “milkmaid dress” is constructed by floral prints, a soft bunching of fabric at the bust, and an A-line skirt: a silhouette descending from Dior’s 1947 design.

In 2025, media has been encouraging women to fulfill their duties in the home, in support of their working husbands. With many faces of the “tradwife” movement dressed in Dior’s characteristic design, the “New Look’s” soft femininity has likely been ubiquitously deemed suitable as its defining, idealized attire.

That is not to say that expressing one’s femininity through fashion always equates to social restriction. However, viewing shifting data in both the garment industry and political system, these hyper-feminine clothing styles do not diverge from accompanying conservative values. Fashion has always been impacted by the social beliefs of a period.

Care to share your thoughts?

-------------------------------------

By: Annabella Lawlor

Title: Is the New Look Totally Innocent in Perpetuating the Image of Idealized Femininity?

Sourced From: www.universityoffashion.com/blog/is-the-new-look-totally-innocent-in-perpetuating-the-image-of-idealized-femininity/

Published Date: Sun, 13 Jul 2025 10:00:54 +0000

Read More

FestivalsMusicNew ReleasesArtistsFashion & ClothingVideosPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

FestivalsMusicNew ReleasesArtistsFashion & ClothingVideosPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions